Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the

Tchaikovsky's early separation from his mother caused an emotional trauma that lasted the rest of his life and was intensified by her death from

Tchaikovsky's early separation from his mother caused an emotional trauma that lasted the rest of his life and was intensified by her death from

On 10 June 1859, the 19-year-old Tchaikovsky graduated as a titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. Appointed to the Ministry of Justice, he became a junior assistant within six months and a senior assistant two months after that. He remained a senior assistant for the rest of his three-year civil service career.

Meanwhile, the

On 10 June 1859, the 19-year-old Tchaikovsky graduated as a titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. Appointed to the Ministry of Justice, he became a junior assistant within six months and a senior assistant two months after that. He remained a senior assistant for the rest of his three-year civil service career.

Meanwhile, the  Rubinstein was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent on the whole and cited him as "a composer of genius" in his autobiography. He was less pleased with the more progressive tendencies of some of Tchaikovsky's student work. Nor did he change his opinion as Tchaikovsky's reputation grew. He and Zaremba clashed with Tchaikovsky when he submitted his First Symphony for performance by the

Rubinstein was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent on the whole and cited him as "a composer of genius" in his autobiography. He was less pleased with the more progressive tendencies of some of Tchaikovsky's student work. Nor did he change his opinion as Tchaikovsky's reputation grew. He and Zaremba clashed with Tchaikovsky when he submitted his First Symphony for performance by the

In 1856, while Tchaikovsky was still at the School of Jurisprudence and Anton Rubinstein lobbied aristocrats to form the

In 1856, while Tchaikovsky was still at the School of Jurisprudence and Anton Rubinstein lobbied aristocrats to form the

Another factor that helped Tchaikovsky's music become popular was a shift in attitude among Russian audiences. Whereas they had previously been satisfied with flashy virtuoso performances of technically demanding but musically lightweight works, they gradually began listening with increasing appreciation of the composition itself. Tchaikovsky's works were performed frequently, with few delays between their composition and first performances; the publication from 1867 onward of his songs and great piano music for the home market also helped boost the composer's popularity.

During the late 1860s, Tchaikovsky began to compose operas. His first, '' The Voyevoda'', based on a play by

Another factor that helped Tchaikovsky's music become popular was a shift in attitude among Russian audiences. Whereas they had previously been satisfied with flashy virtuoso performances of technically demanding but musically lightweight works, they gradually began listening with increasing appreciation of the composition itself. Tchaikovsky's works were performed frequently, with few delays between their composition and first performances; the publication from 1867 onward of his songs and great piano music for the home market also helped boost the composer's popularity.

During the late 1860s, Tchaikovsky began to compose operas. His first, '' The Voyevoda'', based on a play by

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time. It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to homosexuality and portray him as a heterosexual, to efforts at analysis by Western biographers.

Biographers have generally agreed that Tchaikovsky was homosexual. He sought the company of other men in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them."Wiley, ''New Grove'' (2001), 25:147. His first love was reportedly Sergey Kireyev, a younger fellow student at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. According to Modest Tchaikovsky, this was Pyotr Ilyich's "strongest, longest and purest love". The degree to which the composer might have felt comfortable with his sexual desires has, however, remained open to debate. It is still unknown whether Tchaikovsky, according to musicologist and biographer David Brown, "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape" or whether, according to Alexander Poznansky, he experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his sexual desires and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage".

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time. It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to homosexuality and portray him as a heterosexual, to efforts at analysis by Western biographers.

Biographers have generally agreed that Tchaikovsky was homosexual. He sought the company of other men in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them."Wiley, ''New Grove'' (2001), 25:147. His first love was reportedly Sergey Kireyev, a younger fellow student at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. According to Modest Tchaikovsky, this was Pyotr Ilyich's "strongest, longest and purest love". The degree to which the composer might have felt comfortable with his sexual desires has, however, remained open to debate. It is still unknown whether Tchaikovsky, according to musicologist and biographer David Brown, "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape" or whether, according to Alexander Poznansky, he experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his sexual desires and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage".

Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's same-sex attraction, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it. Such censorship has persisted in the Russian government, resulting in many officials, including the former culture minister

Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's same-sex attraction, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it. Such censorship has persisted in the Russian government, resulting in many officials, including the former culture minister

Tchaikovsky remained abroad for a year after the disintegration of his marriage. During this time, he completed ''Eugene Onegin'', orchestrated his Fourth Symphony, and composed the

Tchaikovsky remained abroad for a year after the disintegration of his marriage. During this time, he completed ''Eugene Onegin'', orchestrated his Fourth Symphony, and composed the

In 1884, Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and restlessness. That March, Emperor Alexander III conferred upon him the

In 1884, Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and restlessness. That March, Emperor Alexander III conferred upon him the  Despite Tchaikovsky's disdain for public life, he now participated in it as part of his increasing celebrity and out of a duty he felt to promote Russian music. He helped support his former pupil

Despite Tchaikovsky's disdain for public life, he now participated in it as part of his increasing celebrity and out of a duty he felt to promote Russian music. He helped support his former pupil

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived at Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived at Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the

Of Tchaikovsky's Western predecessors, Robert Schumann stands out as an influence in formal structure, harmonic practices and piano writing, according to Brown and musicologist Roland John Wiley.

Of Tchaikovsky's Western predecessors, Robert Schumann stands out as an influence in formal structure, harmonic practices and piano writing, according to Brown and musicologist Roland John Wiley.

As mentioned above, repetition was a natural part of Tchaikovsky's music, just as it is an integral part of Russian music. His use of

As mentioned above, repetition was a natural part of Tchaikovsky's music, just as it is an integral part of Russian music. His use of

Tchaikovsky's relationship with collaborators was mixed. Like Nikolai Rubinstein with the First Piano Concerto, virtuoso and pedagogue

Tchaikovsky's relationship with collaborators was mixed. Like Nikolai Rubinstein with the First Piano Concerto, virtuoso and pedagogue

Critical reception to Tchaikovsky's music was varied but also improved over time. Even after 1880, some inside Russia held it suspect for not being nationalistic enough and thought Western European critics lauded it for exactly that reason.Botstein, 99. There might have been a grain of truth in the latter, according to musicologist and conductor

Critical reception to Tchaikovsky's music was varied but also improved over time. Even after 1880, some inside Russia held it suspect for not being nationalistic enough and thought Western European critics lauded it for exactly that reason.Botstein, 99. There might have been a grain of truth in the latter, according to musicologist and conductor

Maes and Taruskin write that Tchaikovsky believed that his professionalism in combining skill and high standards in his musical works separated him from his contemporaries in The Five. Maes adds that, like them, he wanted to produce music that reflected Russian national character but which did so to the highest European standards of quality. Tchaikovsky, according to Maes, came along at a time when the nation itself was deeply divided as to what that character truly was. Like his country, Maes writes, it took him time to discover how to express his Russianness in a way that was true to himself and what he had learned. Because of his professionalism, Maes says, he worked hard at this goal and succeeded. The composer's friend, music critic

Maes and Taruskin write that Tchaikovsky believed that his professionalism in combining skill and high standards in his musical works separated him from his contemporaries in The Five. Maes adds that, like them, he wanted to produce music that reflected Russian national character but which did so to the highest European standards of quality. Tchaikovsky, according to Maes, came along at a time when the nation itself was deeply divided as to what that character truly was. Like his country, Maes writes, it took him time to discover how to express his Russianness in a way that was true to himself and what he had learned. Because of his professionalism, Maes says, he worked hard at this goal and succeeded. The composer's friend, music critic

"Critic's Notebook; Defending Tchaikovsky, With Gravity and With Froth"

In ''

Tchaikovsky

' (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). . * Wiley, Roland John, "Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich". In ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition'' (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Sadie, Stanley. . * Wiley, Roland John, ''The Master Musicians: Tchaikovsky'' (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). . * Zhitomirsky, Daniel, "Symphonies". In ''Russian Symphony: Thoughts About Tchaikovsky'' (New York: Philosophical Library, 1947). . * Zajaczkowski, Henry, ''Tchaikovsky's Musical Style'' (Ann Arbor and London: UMI Research Press, 1987). .

Tchaikovsky Research

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich 1840 births 1893 deaths 19th-century classical composers 19th-century journalists 19th-century LGBT people 19th-century male musicians Burials at Tikhvin Cemetery Classical composers of church music Composers for piano Russian people of Ukrainian descent Russian people of French descent Deaths from cholera Honorary Members of the Royal Philharmonic Society Imperial School of Jurisprudence alumni Infectious disease deaths in Russia LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians LGBT Eastern Orthodox Christians LGBT musicians from Russia Male classical pianists Male opera composers Moscow Conservatory academic personnel People from Votkinsk People from Sarapulsky Uyezd Pupils of Nikolai Zaremba Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 4th class Russian ballet composers Russian classical pianists Russian male classical composers Russian music critics Russian music educators Russian untitled nobility Russian opera composers Russian Romantic composers Saint Petersburg Conservatory alumni

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popular concert and theatrical music in the current classical repertoire, including the ballets ''Swan Lake

''Swan Lake'' ( rus, Лебеди́ное о́зеро, r=Lebedínoye ózero, p=lʲɪbʲɪˈdʲinəjə ˈozʲɪrə, link=no ), Op. 20, is a ballet composed by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1875–76. Despite its initial failur ...

'' and ''The Nutcracker

''The Nutcracker'' ( rus, Щелкунчик, Shchelkunchik, links=no ) is an 1892 two-act ballet (""; russian: балет-феерия, link=no, ), originally choreographed by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov with a score by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaiko ...

'', the ''1812 Overture

''The Year 1812, Solemn Overture'', Op. 49, popularly known as the ''1812 Overture'', is a concert overture in E major written in 1880 by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky to commemorate the successful Russian defense against Napoleon ...

'', his First Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

, the ''Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetim ...

'' Overture-Fantasy, several symphonies, and the opera ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, Евгений Оне́гин, ромáн в стихáх, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐˈnʲeɡʲɪn, r=Yevgeniy Onegin, roman v stikhakh) is a novel in verse written by Ale ...

''.

Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant as there was little opportunity for a musical career in Russia at the time and no system of public music education. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory

The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (russian: Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова) (formerly known as th ...

, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching that he received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five with whom his professional relationship was mixed.

Tchaikovsky's training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From that reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style. The principles that governed melody, harmony and other fundamentals of Russian music ran completely counter to those that governed Western European music, which seemed to defeat the potential for using Russian music in large-scale Western composition or for forming a composite style, and it caused personal antipathies that dented Tchaikovsky's self-confidence. Russian culture exhibited a split personality, with its native and adopted elements having drifted apart increasingly since the time of Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

. That resulted in uncertainty among the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

about the country's national identity, an ambiguity mirrored in Tchaikovsky's career.

Despite his many popular successes, Tchaikovsky's life was punctuated by personal crises and depression. Contributory factors included his early separation from his mother for boarding school followed by his mother's early death, the death of his close friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein

Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein (russian: Николай Григорьевич Рубинштейн; – ) was a Russian pianist, conductor, and composer. He was the younger brother of Anton Rubinstein and a close friend of Pyotr Ilyich Tc ...

, his failed marriage with Antonina Miliukova

Antonina Ivanovna Miliukova (russian: Антонина Ивановна Милюкова; – ) was the wife of Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky from 1877 until his death in 1893. After marriage she was known as Antonina Tchaikovskaya. ...

, and the collapse of his 13-year association with the wealthy patroness Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck (russian: Надежда Филаретовна фон Мекк; 13 January 1894) was a Russian businesswoman who became an influential patron of the arts, especially music. She is best known today for her artistic ...

. His homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

, which he kept private, has traditionally also been considered a major factor though some musicologists now downplay its importance. Tchaikovsky's sudden death at the age of 53 is generally ascribed to cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, but there is an ongoing debate as to whether cholera was indeed the cause, and also whether the death was accidental or intentional.

While his music has remained popular among audiences, critical opinions were initially mixed. Some Russians did not feel it was sufficiently representative of native musical values and expressed suspicion that Europeans accepted the music for its Western elements. In an apparent reinforcement of the latter claim, some Europeans lauded Tchaikovsky for offering music more substantive than base exoticism

Exoticism (from "exotic") is a trend in European art and design, whereby artists became fascinated with ideas and styles from distant regions and drew inspiration from them. This often involved surrounding foreign cultures with mystique and fantas ...

and said he transcended stereotypes of Russian classical music. Others dismissed Tchaikovsky's music as "lacking in elevated thought" and derided its formal workings as deficient because they did not stringently follow Western principles.

Life

Childhood

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born on 7 May 1840 inVotkinsk

Votkinsk (russian: Во́ткинск; udm, Вотка, ''Votka'') is an industrial town in the Udmurt Republic, Russia. Population:

History

It was established in April 1759, initially as a center for metallurgical enterprises, and the economic ...

, a small town in Vyatka Governorate

Vyatka Governorate (russian: Вятская губерния, udm, Ватка губерний, mhr, Виче губерний, tt-Cyrl, Вәтке губернасы) was a governorate of the Russian Empire and Russian Soviet Federative Socia ...

(present-day Udmurtia

Udmurtia (russian: Удму́ртия, r=Udmúrtiya, p=ʊˈdmurtʲɪjə; udm, Удмуртия, ''Udmurtija''), or the Udmurt Republic (russian: Удмуртская Республика, udm, Удмурт Республика, Удмурт � ...

) in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, into a family with a long history of military service. His father, Ilya Petrovich Tchaikovsky, had served as a lieutenant colonel and engineer in the Department of Mines,Holden, 4. and would manage the Kamsko-Votkinsk Ironworks. His grandfather, Pyotr Fedorovich Tchaikovsky, was born in the village of Nikolaevka, Yekaterinoslav Governorate

The Yekaterinoslav Governorate (russian: Екатеринославская губерния, Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya; uk, Катеринославська губернія, translit=Katerynoslavska huberniia) or Government of Yekaterinos ...

, Russian Empire (present-day Mykolaivka, Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

), and served first as a physician's assistant in the army and later as city governor of Glazov

Glazov ( rus, Глазов, p=ˈɡlazəf; udm, Глаз, ''Glaz'') is a town in the Udmurt Republic, Russia, located along the Trans-Siberian Railway, on the Cheptsa River. Population:

History

It was first mentioned in the 17th century chr ...

in Vyatka. His great-grandfather, a Zaporozhian Cossack

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

named Fyodor Chaika, distinguished himself under Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

at the Battle of Poltava

The Battle of Poltava; russian: Полта́вская би́тва; uk, Полта́вська би́тва (8 July 1709) was the decisive and largest battle of the Great Northern War. A Russian army under the command of Tsar Peter I defeate ...

in 1709.

Tchaikovsky's mother, Alexandra Andreyevna (née d'Assier), was the second of Ilya's three wives, 18 years her husband's junior and French and German on her father's side. Both Ilya and Alexandra were trained in the arts, including music—a necessity as a posting to a remote area of Russia also meant a need for entertainment, whether in private or at social gatherings.Wiley, ''Tchaikovsky'', 6. Of his six siblings, Tchaikovsky was close to his sister Alexandra and twin brothers Anatoly and Modest. Alexandra's marriage to Lev Davydov would produce seven children and lend Tchaikovsky the only real family life he would know as an adult, especially during his years of wandering.Holden, 43. One of those children, Vladimir Davydov, who went by the nickname 'Bob', would become very close to him.

In 1844, the family hired Fanny Dürbach, a 22-year-old French governess. Four-and-a-half-year-old Tchaikovsky was initially thought too young to study alongside his older brother Nikolai and a niece of the family. His insistence convinced Dürbach otherwise. By the age of six, he had become fluent in French and German. Tchaikovsky also became attached to the young woman; her affection for him was reportedly a counter to his mother's coldness and emotional distance from him, though others assert that the mother doted on her son. Dürbach saved much of Tchaikovsky's work from this period, including his earliest known compositions, and became a source of several childhood anecdotes.

Tchaikovsky began piano lessons at age five. Precocious, within three years he had become as adept at reading sheet music as his teacher. His parents, initially supportive, hired a tutor, bought an orchestrion (a form of barrel organ that could imitate elaborate orchestral effects), and encouraged his piano study for both aesthetic and practical reasons.

However, they decided in 1850 to send Tchaikovsky to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence

The Imperial School of Jurisprudence (Russian: Императорское училище правоведения) was, along with the Page Corps, a school for boys in Saint Petersburg, the capital of the Russian Empire.

The school for would-be ...

in Saint Petersburg. They had both graduated from institutes in Saint Petersburg and the School of Jurisprudence, which mainly served the lesser nobility, and thought that this education would prepare Tchaikovsky for a career as a civil servant. Regardless of talent, the only musical careers available in Russia at that time—except for the affluent aristocracy—were as a teacher in an academy or as an instrumentalist in one of the Imperial Theaters. Both were considered on the lowest rank of the social ladder, with individuals in them enjoying no more rights than peasants.

His father's income was also growing increasingly uncertain, so both parents may have wanted Tchaikovsky to become independent as soon as possible. As the minimum age for acceptance was 12 and Tchaikovsky was only 10 at the time, he was required to spend two years boarding at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence's preparatory school, from his family. Once those two years had passed, Tchaikovsky transferred to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence to begin a seven-year course of studies.

Tchaikovsky's early separation from his mother caused an emotional trauma that lasted the rest of his life and was intensified by her death from

Tchaikovsky's early separation from his mother caused an emotional trauma that lasted the rest of his life and was intensified by her death from cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

in 1854, when he was fourteen. The loss of his mother also prompted Tchaikovsky to make his first serious attempt at composition, a waltz

The waltz ( ), meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom and folk dance, normally in triple ( time), performed primarily in closed position.

History

There are many references to a sliding or gliding dance that would evolve into the wa ...

in her memory. Tchaikovsky's father, who had also contracted cholera but recovered fully, sent him back to school immediately in the hope that classwork would occupy the boy's mind.Holden, 23. Isolated, Tchaikovsky compensated with friendships with fellow students that became lifelong; these included Aleksey Apukhtin

Aleksey Nikolayevich Apukhtin ( rus, Алексе́й Никола́евич Апу́хтин, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ɐˈpuxtʲɪn, a=Alyeksyey Nikolayevich Apuhtin.ru.vorb.oga; – ) was a Russian poet, writer and critic.

...

and Vladimir Gerard.

Music, while not an official priority at school, also bridged the gap between Tchaikovsky and his peers. They regularly attended the opera and Tchaikovsky would improvise at the school's harmonium

The pump organ is a type of free-reed organ that generates sound as air flows past a vibrating piece of thin metal in a frame. The piece of metal is called a reed. Specific types of pump organ include the reed organ, harmonium, and melodeon. T ...

on themes he and his friends had sung during choir practice. "We were amused," Vladimir Gerard later remembered, "but not imbued with any expectations of his future glory". Tchaikovsky also continued his piano studies through Franz Becker, an instrument manufacturer who made occasional visits to the school; however, the results, according to musicologist David Brown, were "negligible".

In 1855, Tchaikovsky's father funded private lessons with Rudolph Kündinger and questioned him about a musical career for his son. While impressed with the boy's talent, Kündinger said he saw nothing to suggest a future composer or performer. He later admitted that his assessment was also based on his own negative experiences as a musician in Russia and his unwillingness for Tchaikovsky to be treated likewise. Tchaikovsky was told to finish his course and then try for a post in the Ministry of Justice.

Civil service; pursuing music

On 10 June 1859, the 19-year-old Tchaikovsky graduated as a titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. Appointed to the Ministry of Justice, he became a junior assistant within six months and a senior assistant two months after that. He remained a senior assistant for the rest of his three-year civil service career.

Meanwhile, the

On 10 June 1859, the 19-year-old Tchaikovsky graduated as a titular counselor, a low rung on the civil service ladder. Appointed to the Ministry of Justice, he became a junior assistant within six months and a senior assistant two months after that. He remained a senior assistant for the rest of his three-year civil service career.

Meanwhile, the Russian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

(RMS) was founded in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (a German-born aunt of Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

Alexander II) and her protégé, pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein ( rus, Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, r=Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who became a pivotal figure in Russian culture when he founded the Sai ...

. Previous tsars and the aristocracy had focused almost exclusively on importing European talent. The aim of the RMS was to fulfil Alexander II's wish to foster native talent. It hosted a regular season of public concerts (previously held only during the six weeks of Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

when the Imperial Theaters were closed) and provided basic professional training in music. In 1861, Tchaikovsky attended RMS classes in music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (ke ...

taught by Nikolai Zaremba

Nikolai or Nicolaus Ivanovich von Zaremba (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Заре́мба; ) was a Russian musical theorist, teacher and composer. His most famous student was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who became his pupil in 1861. Ot ...

at the Mikhailovsky Palace

The Mikhailovsky Palace (russian: Михайловский дворец, tr=Mikhailovskiy dvorets) is a grand ducal palace in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It is located on Arts Square and is an example of Empire style neoclassicism. The palace cu ...

(now the Russian Museum

The State Russian Museum (russian: Государственный Русский музей), formerly the Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III (russian: Русский Музей Императора Александра III), on ...

). These classes were a precursor to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, which opened in 1862. Tchaikovsky enrolled at the Conservatory as part of its premiere class. He studied harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

and counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

with Zaremba and instrumentation and composition with Rubinstein.

The Conservatory benefited Tchaikovsky in two ways. It transformed him into a musical professional, with tools to help him thrive as a composer, and the in-depth exposure to European principles and musical forms gave him a sense that his art was not exclusively Russian or Western.Taruskin, ''Grove Opera'', 4:663–664. This mindset became important in Tchaikovsky's reconciliation of Russian and European influences in his compositional style. He believed and attempted to show that both these aspects were "intertwined and mutually dependent". His efforts became both an inspiration and a starting point for other Russian composers to build their own individual styles.

Rubinstein was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent on the whole and cited him as "a composer of genius" in his autobiography. He was less pleased with the more progressive tendencies of some of Tchaikovsky's student work. Nor did he change his opinion as Tchaikovsky's reputation grew. He and Zaremba clashed with Tchaikovsky when he submitted his First Symphony for performance by the

Rubinstein was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent on the whole and cited him as "a composer of genius" in his autobiography. He was less pleased with the more progressive tendencies of some of Tchaikovsky's student work. Nor did he change his opinion as Tchaikovsky's reputation grew. He and Zaremba clashed with Tchaikovsky when he submitted his First Symphony for performance by the Russian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

in Saint Petersburg. Rubinstein and Zaremba refused to consider the work unless substantial changes were made. Tchaikovsky complied but they still refused to perform the symphony. Tchaikovsky, distressed that he had been treated as though he were still their student, withdrew the symphony. It was given its first complete performance, minus the changes Rubinstein and Zaremba had requested, in Moscow in February 1868.

Once Tchaikovsky graduated in 1865, Rubinstein's brother Nikolai offered him the post of Professor of Music Theory at the soon-to-open Moscow Conservatory

The Moscow Conservatory, also officially Moscow State Tchaikovsky Conservatory (russian: Московская государственная консерватория им. П. И. Чайковского, link=no) is a musical educational inst ...

. While the salary for his professorship was only 50 rubles

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

a month, the offer itself boosted Tchaikovsky's morale and he accepted the post eagerly. He was further heartened by news of the first public performance of one of his works, his ''Characteristic Dances'', conducted by Johann Strauss II

Johann Baptist Strauss II (25 October 1825 – 3 June 1899), also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger or the Son (german: links=no, Sohn), was an Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas. He composed ov ...

at a concert in Pavlovsk Park

The Pavlovsk Park (russian: Павловский парк) is the park surrounding the Pavlovsk Palace, an 18th-century Russian Imperial residence built by Tsar Paul I of Russia near Saint Petersburg. After his death, it became the home of his ...

on 11 September 1865 (Tchaikovsky later included this work, re-titled ''Dances of the Hay Maidens'', in his opera '' The Voyevoda'').

From 1867 to 1878, Tchaikovsky combined his professorial duties with music criticism

''The Oxford Companion to Music'' defines music criticism as "the intellectual activity of formulating judgments on the value and degree of excellence of individual works of music, or whole groups or genres". In this sense, it is a branch of mus ...

while continuing to compose. This activity exposed him to a range of contemporary music and afforded him the opportunity to travel abroad. In his reviews, he praised Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

, considered Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

overrated and, despite his admiration, took Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

to task for poor orchestration. He appreciated the staging of Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the '' Nibe ...

'' at its inaugural performance in Bayreuth

Bayreuth (, ; bar, Bareid) is a town in northern Bavaria, Germany, on the Red Main river in a valley between the Franconian Jura and the Fichtelgebirge Mountains. The town's roots date back to 1194. In the 21st century, it is the capital of U ...

(Germany), but not the music, calling ''Das Rheingold

''Das Rheingold'' (; ''The Rhinegold''), WWV 86A, is the first of the four music dramas that constitute Richard Wagner's ''Der Ring des Nibelungen'' (English: ''The Ring of the Nibelung''). It was performed, as a single opera, at the National ...

'' "unlikely nonsense, through which, from time to time, sparkle unusually beautiful and astonishing details". A recurring theme he addressed was the poor state of Russian opera

Russian opera ( Russian: Ру́сская о́пера ''Rússkaya ópera'') is the art of opera in Russia. Operas by composers of Russian origin, written or staged outside of Russia, also belong to this category, as well as the operas of foreig ...

.

Relationship with The Five

In 1856, while Tchaikovsky was still at the School of Jurisprudence and Anton Rubinstein lobbied aristocrats to form the

In 1856, while Tchaikovsky was still at the School of Jurisprudence and Anton Rubinstein lobbied aristocrats to form the Russian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

, critic Vladimir Stasov

Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov (also Stassov; rus, Влади́мир Васи́льевич Ста́сов; 14 January Adoption_of_the_Gregorian_calendar#Adoption_in_Eastern_Europe.html" ;"title="/nowiki> O.S._2_January.html" ;"title="Adoption of ...

and an 18-year-old pianist, Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (russian: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев,BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian: Miliy Alekseyevich Balakirev; ALA-LC system: ''Miliĭ Alekseevich Balakirev''; ISO 9 system: ''Milij Alekseevič Balakir ...

, met and agreed upon a nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

agenda for Russian music, one that would take the operas of Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, link=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka., mʲɪxɐˈil ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recogni ...

as a model and incorporate elements from folk music, reject traditional Western practices and use non-Western harmonic devices such as the whole tone

In Western music theory, a major second (sometimes also called whole tone or a whole step) is a second spanning two semitones (). A second is a musical interval encompassing two adjacent staff positions (see Interval number for more deta ...

and octatonic scale

An octatonic scale is any eight-note musical scale. However, the term most often refers to the symmetric scale composed of alternating whole and half steps, as shown at right. In classical theory (in contrast to jazz theory), this symmetrical ...

s. They saw Western-style conservatories as unnecessary and antipathetic to fostering native talent.

Eventually, Balakirev, César Cui

César Antonovich Cui ( rus, Це́зарь Анто́нович Кюи́, , ˈt͡sjezərʲ ɐnˈtonəvʲɪt͡ɕ kʲʊˈi, links=no, Ru-Tsezar-Antonovich-Kyui.ogg; french: Cesarius Benjaminus Cui, links=no, italic=no; 13 March 1918) was a Ru ...

, Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

and Alexander Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin ( rus, link=no, Александр Порфирьевич Бородин, Aleksandr Porfir’yevich Borodin , p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr pɐrˈfʲi rʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈdʲin, a=RU-Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin.ogg, ...

became known as the ''moguchaya kuchka'', translated into English as the "Mighty Handful" or "The Five". Rubinstein criticized their emphasis on amateur efforts in musical composition; Balakirev and later Mussorgsky attacked Rubinstein for his musical conservatism and his belief in professional music training. Tchaikovsky and his fellow conservatory students were caught in the middle.

While ambivalent about much of The Five's music, Tchaikovsky remained on friendly terms with most of its members. In 1869, he and Balakirev worked together on what became Tchaikovsky's first recognized masterpiece, the fantasy-overture ''Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetim ...

'', a work which The Five wholeheartedly embraced. The group also welcomed his Second Symphony, subtitled the ''Little Russia

Little Russia (russian: Малороссия/Малая Россия, Malaya Rossiya/Malorossiya; uk, Малоросія/Мала Росія, Malorosiia/Mala Rosiia), also known in English as Malorussia, Little Rus' (russian: Малая Ру� ...

n''. Despite their support, Tchaikovsky made considerable efforts to ensure his musical independence from the group as well as from the conservative faction at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.

Growing fame; budding opera composer

The infrequency of Tchaikovsky's musical successes, won with tremendous effort, exacerbated his lifelong sensitivity to criticism. Nikolai Rubinstein's private fits of rage critiquing his music, such as attacking the First Piano Concerto, did not help matters. His popularity grew, however, as several first-rate artists became willing to perform his compositions.Hans von Bülow

Freiherr Hans Guido von Bülow (8 January 1830 – 12 February 1894) was a German conductor, virtuoso pianist, and composer of the Romantic era. As one of the most distinguished conductors of the 19th century, his activity was critical for es ...

premiered the First Piano Concerto and championed other Tchaikovsky works both as pianist and conductor. Other artists included Adele aus der Ohe, Max Erdmannsdörfer

Max Erdmannsdörfer (14 June 184814 February 1905) (sometimes seen as ''Max von Erdmannsdörfer'') was a German conductor, pianist and composer.

He was born in Nuremberg. He studied at the Leipzig Conservatory, becoming concertmaster at Sonders ...

, Eduard Nápravník

Eduard Francevič Nápravník (Russian: Эдуа́рд Фра́нцевич Напра́вник; 24 August 1839 – 10 November 1916) was a Czech conductor and composer. Nápravník settled in Russia and is best known for his leading role in Rus ...

and Sergei Taneyev

Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev (russian: Серге́й Ива́нович Тане́ев, ; – ) was a Russian composer, pianist, teacher of composition, music theorist and author.

Life

Taneyev was born in Vladimir, Vladimir Governorate, Russia ...

.

Another factor that helped Tchaikovsky's music become popular was a shift in attitude among Russian audiences. Whereas they had previously been satisfied with flashy virtuoso performances of technically demanding but musically lightweight works, they gradually began listening with increasing appreciation of the composition itself. Tchaikovsky's works were performed frequently, with few delays between their composition and first performances; the publication from 1867 onward of his songs and great piano music for the home market also helped boost the composer's popularity.

During the late 1860s, Tchaikovsky began to compose operas. His first, '' The Voyevoda'', based on a play by

Another factor that helped Tchaikovsky's music become popular was a shift in attitude among Russian audiences. Whereas they had previously been satisfied with flashy virtuoso performances of technically demanding but musically lightweight works, they gradually began listening with increasing appreciation of the composition itself. Tchaikovsky's works were performed frequently, with few delays between their composition and first performances; the publication from 1867 onward of his songs and great piano music for the home market also helped boost the composer's popularity.

During the late 1860s, Tchaikovsky began to compose operas. His first, '' The Voyevoda'', based on a play by Alexander Ostrovsky

Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Остро́вский; ) was a Russian playwright, generally considered the greatest representative of the Russian realistic period. The author of 47 origina ...

, premiered in 1869. The composer became dissatisfied with it, however, and, having re-used parts of it in later works, destroyed the manuscript. ''Undina

Undines (; also ondines) are a category of elemental beings associated with water, stemming from the alchemical writings of Paracelsus. Later writers developed the undine into a water nymph in its own right, and it continues to live in modern li ...

'' followed in 1870. Only excerpts were performed and it, too, was destroyed.Taruskin, 665. Between these projects, Tchaikovsky started to compose an opera called ''Mandragora'', to a libretto by Sergei Rachinskii; the only music he completed was a short chorus of Flowers and Insects.

The first Tchaikovsky opera to survive intact, ''The Oprichnik

''The Oprichnik'' or ''The Guardsman'' (russian: Опричник ) is an opera in 4 acts, 5 scenes, by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky to his own libretto after the tragedy ''The Oprichniks'' ( rus, Опричники) by Ivan Lazhechnikov (1792–1869) ...

'', premiered in 1874. During its composition, he lost Ostrovsky's part-finished libretto. Tchaikovsky, too embarrassed to ask for another copy, decided to write the libretto himself, modelling his dramatic technique on that of Eugène Scribe

Augustin Eugène Scribe (; 24 December 179120 February 1861) was a French dramatist and librettist. He is known for writing "well-made plays" ("pièces bien faites"), a mainstay of popular theatre for over 100 years, and as the librettist of man ...

. Cui wrote a "characteristically savage press attack" on the opera. Mussorgsky, writing to Vladimir Stasov

Vladimir Vasilievich Stasov (also Stassov; rus, Влади́мир Васи́льевич Ста́сов; 14 January Adoption_of_the_Gregorian_calendar#Adoption_in_Eastern_Europe.html" ;"title="/nowiki> O.S._2_January.html" ;"title="Adoption of ...

, disapproved of the opera as pandering to the public. Nevertheless, ''The Oprichnik'' continues to be performed from time to time in Russia.

The last of the early operas, ''Vakula the Smith

''Vakula the Smith'' (russian: Кузнец Вакула, Kuznéts Vakúla, Smith Vakula ), Op. 14, is a Ukrainian-themed opera in 3 acts, 8 scenes, by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The libretto was written by Yakov Polonsky and is based on Nikolai G ...

'' (Op. 14), was composed in the second half of 1874. The libretto, based on Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

's ''Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve is the evening or entire day before Christmas Day, the festival commemorating the birth of Jesus. Christmas Day is observed around the world, and Christmas Eve is widely observed as a full or partial holiday in anticipation ...

'', was to have been set to music by Alexander Serov

Alexander Nikolayevich Serov (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Серо́в, Saint Petersburg, – Saint Petersburg, ) was a Russian composer and music critic. He is notable as one of the most important music critics in ...

. With Serov's death, the libretto was opened to a competition with a guarantee that the winning entry would be premiered by the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

The Mariinsky Theatre ( rus, Мариинский театр, Mariinskiy teatr, also transcribed as Maryinsky or Mariyinsky) is a historic theatre of opera and ballet in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Opened in 1860, it became the preeminent music th ...

. Tchaikovsky was declared the winner, but at the 1876 premiere, the opera enjoyed only a lukewarm reception. After Tchaikovsky's death, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote the opera ''Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve is the evening or entire day before Christmas Day, the festival commemorating the birth of Jesus. Christmas Day is observed around the world, and Christmas Eve is widely observed as a full or partial holiday in anticipation ...

'', based on the same story.

Other works of this period include the '' Variations on a Rococo Theme'' for cello and orchestra, the Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

and Fourth Symphonies, the ballet ''Swan Lake

''Swan Lake'' ( rus, Лебеди́ное о́зеро, r=Lebedínoye ózero, p=lʲɪbʲɪˈdʲinəjə ˈozʲɪrə, link=no ), Op. 20, is a ballet composed by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1875–76. Despite its initial failur ...

'', and the opera ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, Евгений Оне́гин, ромáн в стихáх, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐˈnʲeɡʲɪn, r=Yevgeniy Onegin, roman v stikhakh) is a novel in verse written by Ale ...

''.

Personal life

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time. It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to homosexuality and portray him as a heterosexual, to efforts at analysis by Western biographers.

Biographers have generally agreed that Tchaikovsky was homosexual. He sought the company of other men in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them."Wiley, ''New Grove'' (2001), 25:147. His first love was reportedly Sergey Kireyev, a younger fellow student at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. According to Modest Tchaikovsky, this was Pyotr Ilyich's "strongest, longest and purest love". The degree to which the composer might have felt comfortable with his sexual desires has, however, remained open to debate. It is still unknown whether Tchaikovsky, according to musicologist and biographer David Brown, "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape" or whether, according to Alexander Poznansky, he experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his sexual desires and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage".

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time. It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to homosexuality and portray him as a heterosexual, to efforts at analysis by Western biographers.

Biographers have generally agreed that Tchaikovsky was homosexual. He sought the company of other men in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them."Wiley, ''New Grove'' (2001), 25:147. His first love was reportedly Sergey Kireyev, a younger fellow student at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. According to Modest Tchaikovsky, this was Pyotr Ilyich's "strongest, longest and purest love". The degree to which the composer might have felt comfortable with his sexual desires has, however, remained open to debate. It is still unknown whether Tchaikovsky, according to musicologist and biographer David Brown, "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape" or whether, according to Alexander Poznansky, he experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his sexual desires and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage".

Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's same-sex attraction, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it. Such censorship has persisted in the Russian government, resulting in many officials, including the former culture minister

Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's same-sex attraction, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it. Such censorship has persisted in the Russian government, resulting in many officials, including the former culture minister Vladimir Medinsky

Vladimir Rostislavovich Medinsky (russian: link=no, Владимир Ростиславович Мединский, uk, Володимир Ростиславович Мединський; born July 18, 1970) is a Russian political figure, acad ...

, denying his homosexuality outright. Passages in Tchaikovsky's letters which reveal his homosexual desires have been censored in Russia. In one such passage he said of a homosexual acquaintance: "Petashenka used to drop by with the criminal intention of observing the Cadet Corps, which is right opposite our windows, but I've been trying to discourage these compromising visits—and with some success." In another one he wrote: "After our walk, I offered him some money, which was refused. He does it for the love of art and adores men with beards."

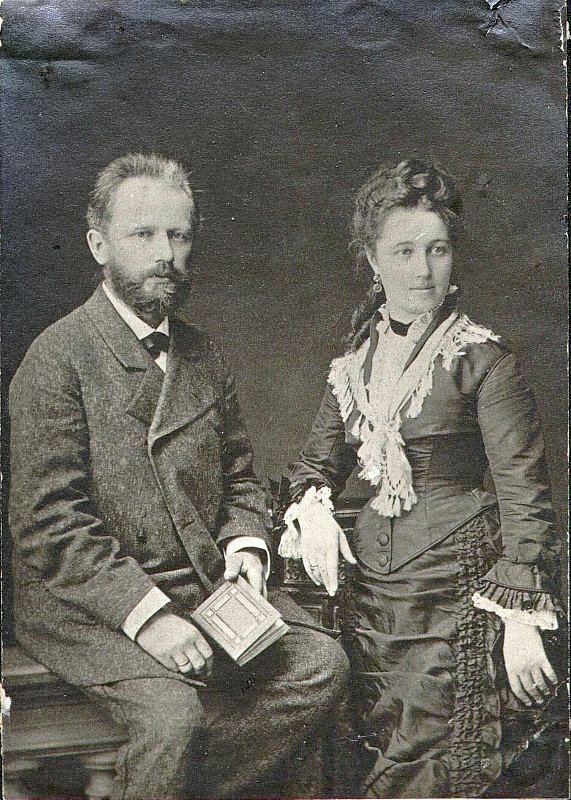

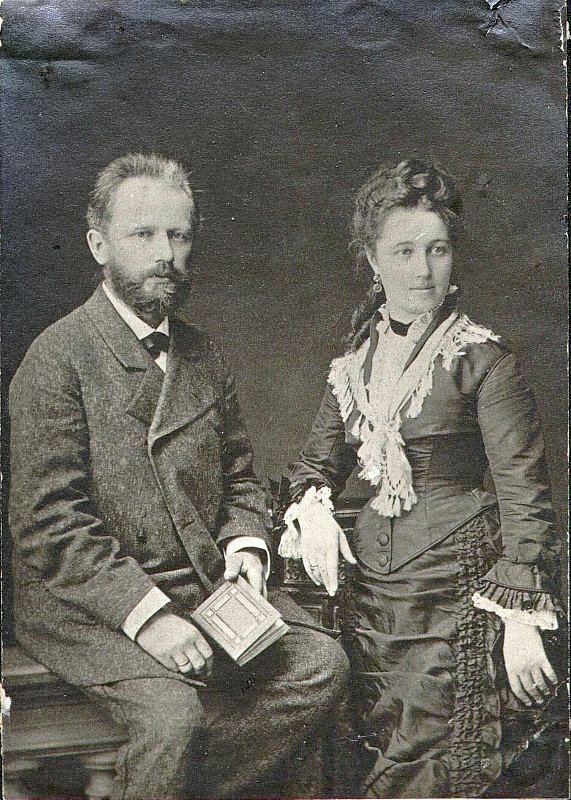

Tchaikovsky lived as a bachelor for most of his life. In 1868, he met Belgian soprano Désirée Artôt

Désirée Artôt (; 21 July 1835 – 3 April 1907) was a Belgian soprano (initially a mezzo-soprano), who was famed in German and Italian opera and sang mainly in Germany. In 1868 she was engaged, briefly, to Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who may h ...

with whom he considered marriage, but, owing to various circumstances, the relationship ended. Tchaikovsky later claimed she was the only woman he ever loved. In 1877, at the age of 37, he wed a former student, Antonina Miliukova

Antonina Ivanovna Miliukova (russian: Антонина Ивановна Милюкова; – ) was the wife of Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky from 1877 until his death in 1893. After marriage she was known as Antonina Tchaikovskaya. ...

.Brown, ''The Crisis Years'', 137–147; Polayansky, ''Quest'', 207–208, 219–220; Wiley, ''Tchaikovsky'', 147–150. The marriage was a disaster. Mismatched psychologically and sexually,Brown, ''The Crisis Years'', 146–148; Poznansky, ''Quest'', 234; Wiley, ''Tchaikovsky'', 152. the couple lived together for only two and a half months before Tchaikovsky left, overwrought emotionally and suffering from acute writer's block

Writer's block is a condition, primarily associated with writing, in which an author is either unable to produce new work or experiences a creative slowdown. Mike Rose found that this creative stall is not a result of commitment problems or th ...

.Brown, ''The Crisis Years'', 157; Poznansky, ''Quest'', 234; Wiley, ''Tchaikovsky'', 155. Tchaikovsky's family remained supportive of him during this crisis and throughout his life. Tchaikovsky's marital debacle may have forced him to face the full truth about his sexuality; he never blamed Antonina for the failure of their marriage.

He was also aided by Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck (russian: Надежда Филаретовна фон Мекк; 13 January 1894) was a Russian businesswoman who became an influential patron of the arts, especially music. She is best known today for her artistic ...

, the widow of a railway magnate, who had begun contact with him not long before the marriage. As well as an important friend and emotional support,Holden, 159, 231–232. she became his patroness for the next 13 years, which allowed him to focus exclusively on composition.Brown, ''Man and Music'', 171–172. Although Tchaikovsky called her his "best friend", they agreed to never meet under any circumstances.

Years of wandering

Tchaikovsky remained abroad for a year after the disintegration of his marriage. During this time, he completed ''Eugene Onegin'', orchestrated his Fourth Symphony, and composed the

Tchaikovsky remained abroad for a year after the disintegration of his marriage. During this time, he completed ''Eugene Onegin'', orchestrated his Fourth Symphony, and composed the Violin Concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

. He returned briefly to the Moscow Conservatory in the autumn of 1879. For the next few years, assured of a regular income from von Meck, he traveled incessantly throughout Europe and rural Russia, mainly alone, and avoided social contact whenever possible.Brown, ''Man and Music'', 219.

During this time, Tchaikovsky's foreign reputation grew and a positive reassessment of his music also took place in Russia, thanks in part to Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

's call for "universal unity" with the West at the unveiling of the Pushkin Monument in Moscow in 1880. Before Dostoevsky's speech, Tchaikovsky's music had been considered "overly dependent on the West". As Dostoevsky's message spread throughout Russia, this stigma toward Tchaikovsky's music evaporated.Volkov, 126. The unprecedented acclaim for him even drew a cult following among the young intelligentsia of Saint Petersburg, including Alexandre Benois

Alexandre Nikolayevich Benois (russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Бенуа́, also spelled Alexander Benois; ,Salmina-Haskell, Larissa. ''Russian Paintings and Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum''. pp. 15, 23-24. Published by ...

, Léon Bakst

Léon Bakst (russian: Леон (Лев) Николаевич Бакст, Leon (Lev) Nikolaevich Bakst) – born as Leyb-Khaim Izrailevich (later Samoylovich) Rosenberg, Лейб-Хаим Израилевич (Самойлович) Розенбе ...

and Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev ( ; rus, Серге́й Па́влович Дя́гилев, , sʲɪˈrɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪdʑ ˈdʲæɡʲɪlʲɪf; 19 August 1929), usually referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic, pat ...

.

Two musical works from this period stand out. With the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour ( rus, Храм Христа́ Спаси́теля, r=Khram Khristá Spasítelya, p=xram xrʲɪˈsta spɐˈsʲitʲɪlʲə) is a Russian Orthodox cathedral in Moscow, Russia, on the northern bank of the Moskv ...

nearing completion in Moscow in 1880, the 25th anniversary of the coronation of Alexander II in 1881, and the 1882 Moscow Arts and Industry Exhibition in the planning stage, Nikolai Rubinstein

Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein (russian: Николай Григорьевич Рубинштейн; – ) was a Russian pianist, conductor, and composer. He was the younger brother of Anton Rubinstein and a close friend of Pyotr Ilyich Tc ...

suggested that Tchaikovsky compose a grand commemorative piece. Tchaikovsky agreed and finished it within six weeks. He wrote to Nadezhda von Meck

Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck (russian: Надежда Филаретовна фон Мекк; 13 January 1894) was a Russian businesswoman who became an influential patron of the arts, especially music. She is best known today for her artistic ...

that this piece, the ''1812 Overture

''The Year 1812, Solemn Overture'', Op. 49, popularly known as the ''1812 Overture'', is a concert overture in E major written in 1880 by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky to commemorate the successful Russian defense against Napoleon ...

'', would be "very loud and noisy, but I wrote it with no warm feeling of love, and therefore there will probably be no artistic merits in it".As quoted in Brown, ''The Years of Wandering'', 119. He also warned conductor Eduard Nápravník

Eduard Francevič Nápravník (Russian: Эдуа́рд Фра́нцевич Напра́вник; 24 August 1839 – 10 November 1916) was a Czech conductor and composer. Nápravník settled in Russia and is best known for his leading role in Rus ...

that "I shan't be at all surprised and offended if you find that it is in a style unsuitable for symphony concerts". Nevertheless, the overture became, for many, "the piece by Tchaikovsky they know best",Brown, ''Man and Music'', 224. particularly well-known for the use of cannon in the scores.

On 23 March 1881, Nikolai Rubinstein died in Paris. That December, Tchaikovsky started work on his Piano Trio in A minor, "dedicated to the memory of a great artist". First performed privately at the Moscow Conservatory on the first anniversary of Rubinstein's death, the piece became extremely popular during the composer's lifetime; in November 1893, it would become Tchaikovsky's own elegy at memorial concerts in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Return to Russia

In 1884, Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and restlessness. That March, Emperor Alexander III conferred upon him the

In 1884, Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and restlessness. That March, Emperor Alexander III conferred upon him the Order of Saint Vladimir

The Imperial Order of Saint Prince Vladimir (russian: орден Святого Владимира) was an Imperial Russian order established on by Empress Catherine II in memory of the deeds of Saint Vladimir, the Grand Prince and the Baptize ...

(fourth class), which included a title of hereditary nobility and a personal audience with the Tsar. This was seen as a seal of official approval which advanced Tchaikovsky's social standingBrown, ''New Grove'' vol. 18, p. 621; Holden, 233. and might have been cemented in the composer's mind by the success of his Orchestral Suite No. 3 at its January 1885 premiere in Saint Petersburg.Brown, ''Man and Music'', 275.

In 1885, Alexander III requested a new production of ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, Евгений Оне́гин, ромáн в стихáх, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐˈnʲeɡʲɪn, r=Yevgeniy Onegin, roman v stikhakh) is a novel in verse written by Ale ...

'' at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

The Saint Petersburg Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre (The Big Stone Theatre of Saint Petersburg, russian: Большой Каменный Театр) was a theatre in Saint Petersburg.

It was built in 1783 to Antonio Rinaldi's Neoclassical ...

in Saint Petersburg. By having the opera staged there and not at the Mariinsky Theatre

The Mariinsky Theatre ( rus, Мариинский театр, Mariinskiy teatr, also transcribed as Maryinsky or Mariyinsky) is a historic theatre of opera and ballet in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Opened in 1860, it became the preeminent music th ...

, he served notice that Tchaikovsky's music was replacing Italian opera

Italian opera is both the art of opera in Italy and opera in the Italian language. Opera was born in Italy around the year 1600 and Italian opera has continued to play a dominant role in the history of the form until the present day. Many famous ...

as the official imperial art. In addition, at the instigation of Ivan Vsevolozhsky

Ivan Alexandrovich Vsevolozhsky (russian: Иван Александрович Всеволожский; 1835–1909) was the Director of the Imperial Theatres in Russia from 1881–98 and director of the Hermitage from 1899 to his death in 190 ...

, Director of the Imperial Theaters and a patron of the composer, Tchaikovsky was awarded a lifetime annual pension of 3,000 rubles from the Tsar. This made him the premier court composer, in practice if not in actual title.

Despite Tchaikovsky's disdain for public life, he now participated in it as part of his increasing celebrity and out of a duty he felt to promote Russian music. He helped support his former pupil

Despite Tchaikovsky's disdain for public life, he now participated in it as part of his increasing celebrity and out of a duty he felt to promote Russian music. He helped support his former pupil Sergei Taneyev

Sergey Ivanovich Taneyev (russian: Серге́й Ива́нович Тане́ев, ; – ) was a Russian composer, pianist, teacher of composition, music theorist and author.

Life

Taneyev was born in Vladimir, Vladimir Governorate, Russia ...

, who was now director of Moscow Conservatory, by attending student examinations and negotiating the sometimes sensitive relations among various members of the staff. He served as director of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society

The Russian Musical Society (RMS) (russian: Русское музыкальное общество) was the first music school in Russia open to the general public. It was launched in 1859 by the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna and Anton Rubinstei ...

during the 1889–1890 season. In this post, he invited many international celebrities to conduct, including Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid- Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped wit ...

, Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák ( ; ; 8 September 1841 – 1 May 1904) was a Czechs, Czech composer. Dvořák frequently employed rhythms and other aspects of the folk music of Moravian traditional music, Moravia and his native Bohemia, following t ...

and Jules Massenet

Jules Émile Frédéric Massenet (; 12 May 1842 – 13 August 1912) was a French composer of the Romantic era best known for his operas, of which he wrote more than thirty. The two most frequently staged are '' Manon'' (1884) and ''Werther' ...

.Wiley, ''New Grove'' (2001), 25:162.

During this period, Tchaikovsky also began promoting Russian music as a conductor, In January 1887, he substituted, on short notice, at the Bolshoi Theater

The Bolshoi Theatre ( rus, Большо́й теа́тр, r=Bol'shoy teatr, literally "Big Theater", p=bɐlʲˈʂoj tʲɪˈatər) is a historic theatre in Moscow, Russia, originally designed by architect Joseph Bové, which holds ballet and ope ...

in Moscow for performances of his opera ''Cherevichki

''Cherevichki'' (russian: Черевички , ua, Черевички, ''Cherevichki'', ''Čerevički'', ''The Slippers''; alternative renderings are ''The Little Shoes'', ''The Tsarina's Slippers'', ''The Empress's Slippers'', ''The Golden Slippe ...

''. Within a year, he was in considerable demand throughout Europe and Russia. These appearances helped him overcome life-long stage fright

Stage fright or performance anxiety is the anxiety, fear, or persistent phobia which may be aroused in an individual by the requirement to perform in front of an audience, real or imagined, whether actually or potentially (for example, when perf ...

and boosted his self-assurance. In 1888, Tchaikovsky led the premiere of his Fifth Symphony in Saint Petersburg, repeating the work a week later with the first performance of his tone poem ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

''. Although critics proved hostile, with César Cui

César Antonovich Cui ( rus, Це́зарь Анто́нович Кюи́, , ˈt͡sjezərʲ ɐnˈtonəvʲɪt͡ɕ kʲʊˈi, links=no, Ru-Tsezar-Antonovich-Kyui.ogg; french: Cesarius Benjaminus Cui, links=no, italic=no; 13 March 1918) was a Ru ...

calling the symphony "routine" and "meretricious", both works were received with extreme enthusiasm by audiences and Tchaikovsky, undeterred, continued to conduct the symphony in Russia and Europe. Conducting brought him to the United States in 1891, where he led the New York Music Society's orchestra in his ''Festival Coronation March'' at the inaugural concert of Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

.

Belyayev circle and growing reputation

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived at Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky arrived at Saint Petersburg in time to hear several of the Russian Symphony Concerts The Russian Symphony Concerts were a series of Russian classical music concerts hosted by timber magnate and musical philanthropist Mitrofan Belyayev in St. Petersburg as a forum for young Russian composers to have their orchestral works performed. ...

, devoted exclusively to the music of Russian composers. One included the first complete performance of his revised First Symphony; another featured the final version of Third Symphony of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

, with whose circle Tchaikovsky was already in touch.

Rimsky-Korsakov, with Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov; ger, Glasunow (, 10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 ...

, Anatoly Lyadov

Anatoly Konstantinovich Lyadov (russian: Анато́лий Константи́нович Ля́дов; ) was a Russian composer, teacher, and conductor (music), conductor.

Biography

Lyadov was born in 1855 in Saint Petersburg, St. Petersbur ...

and several other nationalistically minded composers and musicians, had formed a group known as the Belyayev circle

The Belyayev circle (russian: Беляевский кружок) was a society of Russian musicians who met in Saint Petersburg, Russia between 1885 and 1908, and whose members included Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Alexander Glazunov, Vladimir Stasov, ...

, named after a merchant and amateur musician who became an influential music patron and publisher. Tchaikovsky spent much time in this circle, becoming far more at ease with them than he had been with the 'Five' and increasingly confident in showcasing his music alongside theirs. This relationship lasted until Tchaikovsky's death.Poznansky, ''Quest'', 564.

In 1892, Tchaikovsky was voted a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

in France, only the second Russian subject to be so honored (the first was sculptor Mark Antokolsky

Mark Matveyevich Antokolsky (russian: Марк Матве́евич Антоко́льский; 2 November 18409 July 1902) was a Russian Imperial sculptor of Lithuanian Jewish descent.

Biography

Mordukh Matysovich Antokolsky''Boris Schatz: The ...

). The following year, the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in England awarded Tchaikovsky an honorary Doctor of Music

The Doctor of Music degree (D.Mus., D.M., Mus.D. or occasionally Mus.Doc.) is a higher doctorate awarded on the basis of a substantial portfolio of compositions and/or scholarly publications on music. Like other higher doctorates, it is granted b ...

degree.

Death

On 16/28 October 1893, Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, the ''Pathétique'', in Saint Petersburg. Nine days later, Tchaikovsky died there, aged 53. He was interred inTikhvin Cemetery

Tikhvin Cemetery (russian: Тихвинское кладбище) is a historic cemetery in the centre of Saint Petersburg. It is part of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, and is one of four cemeteries in the complex. Since 1932 it has been part of the ...

at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery

Saint Alexander Nevsky Lavra or Saint Alexander Nevsky Monastery was founded by Peter I of Russia in 1710 at the eastern end of the Nevsky Prospekt in Saint Petersburg, in the belief that this was the site of the Neva Battle in 1240 when Alex ...

, near the graves of fellow-composers Alexander Borodin

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin ( rus, link=no, Александр Порфирьевич Бородин, Aleksandr Porfir’yevich Borodin , p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr pɐrˈfʲi rʲjɪvʲɪtɕ bərɐˈdʲin, a=RU-Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin.ogg, ...

, Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, link=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka., mʲɪxɐˈil ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recogni ...

, and Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

; later, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

and Mily Balakirev

Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev (russian: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев,BGN/PCGN transliteration of Russian: Miliy Alekseyevich Balakirev; ALA-LC system: ''Miliĭ Alekseevich Balakirev''; ISO 9 system: ''Milij Alekseevič Balakir ...

were also buried nearby.

While Tchaikovsky's death has traditionally been attributed to cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

from drinking unboiled water at a local restaurant, there has been much speculation that his death was suicide.Brown, ''Man and Music'', 431–435; Holden, 373–400. In the ''New Grove Dictionary of Music